10 Items or Less opens Friday in theaters. But if you wait two weeks, you can download it onto your computer. For producer-star Morgan Freeman, it's part of a plan to level the playing field between Hollywood studios and indie distributors.

10 Items or Less opens Friday in theaters. But if you wait two weeks, you can download it onto your computer. For producer-star Morgan Freeman, it's part of a plan to level the playing field between Hollywood studios and indie distributors.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Coming soon to a monitor near you

10 Items or Less opens Friday in theaters. But if you wait two weeks, you can download it onto your computer. For producer-star Morgan Freeman, it's part of a plan to level the playing field between Hollywood studios and indie distributors.

10 Items or Less opens Friday in theaters. But if you wait two weeks, you can download it onto your computer. For producer-star Morgan Freeman, it's part of a plan to level the playing field between Hollywood studios and indie distributors.

More Sundacing

IndieWire has the rest of the Sundance '07 lineup. Of particular interest: Craig Brewer's follow-up to Hustle and Flow, new films by indie stalwarts Tom DiCillo and Hal Hartley -- and the final feature directed by the recently murdered Adrienne Shelly.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

'Apocalypto' now

For what it's worth: An acquaintance who's not given to excessive hyperbole -- but who is a pretty savvy industry observer -- called me today after seeing an early screening of Apocalypto. The verdict: "Amazing. You've never seen anything like it." Consider yourself forewarned: This year's Oscar race may be about to change...

For what it's worth: An acquaintance who's not given to excessive hyperbole -- but who is a pretty savvy industry observer -- called me today after seeing an early screening of Apocalypto. The verdict: "Amazing. You've never seen anything like it." Consider yourself forewarned: This year's Oscar race may be about to change...

Sundance '07: The frenzy begins

IndieWire has the scoop: The Sundance Film Festival has announced its competition lineup for 2007.

IndieWire has the scoop: The Sundance Film Festival has announced its competition lineup for 2007.

DeVito's drunken diatribe

Gosh! Do you think he started hitting the bottle after he read the reviews for Deck the Halls?

Post No. 200: Kim loves Godzilla (and Clint and Whitney)

For the 200th posting on this blog, I take -- well, pride probably isn't the right word in this context. Amusement, maybe? In any event: Kim Jong Il may not be able to get new films from Netflix after all if President Bush has his way. And that's a pity, because, as the Associated Press reports, Kim "is said to own an extensive movie library of more than 10,000 titles and prefers films about James Bond and Godzilla, along with Clint Eastwood's 1993 drama, In the Line of Fire, and Whitney Houston's 1992 love story, The Bodyguard." Maybe somebody will slip him a DVD of Casino Royale in return for a promise not to build nukes? (That is, unless Kim soured on 007 after seeing Die Another Day.) Or perhaps all great dictators really prefer Mickey Mouse?

Ode to Noiret

In LA Weekly, Bertrand Tavernier -- director of Coup de Torchon and Life and Nothing But, Philippe Noiret's greatest films -- fondly remembers the actor he describes as "a friend, a brother, a father." (Thanks to Movie City News for the head's up.)

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Grand 'Motel'

At the risk of sounding presumptuous at best, paternalistic at worst, I must confess to stirrings of pride as I see Michael Kang's The Motel listed among the five nominees in the Best First Feature category of Film Independent's Spirit Awards. I wrote one of the earliest reviews for this excellent indie when I covered it for Variety at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival. And I've been raving about it ever since to anyone willing to listen. If I helped in any small way to attract some attention for this sleeper -- which I seriously doubt, but please indulge me -- well, I'm a very happy camper indeed.

At the risk of sounding presumptuous at best, paternalistic at worst, I must confess to stirrings of pride as I see Michael Kang's The Motel listed among the five nominees in the Best First Feature category of Film Independent's Spirit Awards. I wrote one of the earliest reviews for this excellent indie when I covered it for Variety at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival. And I've been raving about it ever since to anyone willing to listen. If I helped in any small way to attract some attention for this sleeper -- which I seriously doubt, but please indulge me -- well, I'm a very happy camper indeed.As I noted in Variety: Kang covers some familiar territory in this coming-of-age dramedy about a precocious Chinese-American youth whose family operates a sleazy roadside motel in upstate New York. But Kang manages to stake his own claim to a patch of that well-trod ground by offering a fresh take on characters and conventions, and compelling interest with shrewd, sympathy-inspiring storytelling. In short, The Motel signals the arrival of a singularly talented filmmaker.

Newcomer Jeffrey Chyau impresses with an unaffected yet engagingly expressive performance as 13-year-old Ernest, an overweight daydreamer and budding writer who lives with his cranky mother (Jade Wu), annoying kid sister (Alexis Chang) and ancient grandfather (Stephen Chen) in their family-run motor inn. Ever since his father abandoned them, Ernest has shouldered most of the everyday maintenance responsibilities. Which means that, each day after school, he gets graphic lessons in the seedier aspects of life while cleaning rent-by-the-hour rooms used mostly for illicit trysts.

Working from the novel Waylaid by Ed Lin, Kang emphasizes character detail over plot development, so that the loose-knit narrative evolves as a steady accumulation of sharply-observed, vividly-rendered details. When he isn’t avoiding the bellicose son of long-term residents -- a family even more dysfunctional than his own -- Ernest nurses a crush on Christine (Samantha Futerman), a slightly older teen waitress at nearby Chinese restaurant. Although Christine wants to remain “just friends,” she offers sincere congratulations when Ernest wins “honorable mention” in a local essay contest. But Ernest’s mother is far less supportive – she cruelly mocks her son for his literary ambitions, venting pent-up rage she feels over being abandoned by her husband.

Much of Motel pivots on the budding friendship between Ernest and Sam, a smooth-talking, sharp-dressing Korean-American twentysomething who checks into the motel for a quickie with a hooker, then remains as a long-term renter. Sam, charismatically played by Sung Kang (Better Luck Tomorrow), apparently views his stay at the seedy inn as a self-imposed exile in the wake of a messy break-up with his girlfriend. For all his bad habits – or, more likely, because of them – this obvious ne’er-do-well becomes a surrogate big brother for Ernest, imparting dubious wisdom while trying to prepare the fatherless adolescent for manhood. Not surprisingly, life lessons are taken to heart, with mixed results.

Taking his cue from Francois Truffaut, his most obvious influence, Kang refrains from making any character an out-and-out villain. Even the bully who torments Ernest is as much a victim as a victimizer. And Ernest’s mother, though embittered and often shrewish, has ample reason for her rancor. (Of course, it helps a lot that Jade Wu gives the role enough complexity to prevent the character from curdling into caricature.) But be forewarned: When she berates her son for wanting to tell stories – which, in her mind, is tantamount to lying – more than a few writers in the audience (and not just children of tradition-bound immigrant parents) will wince while remembering similar childhood experiences with disapproving parents.

BTW: The Motel continues to appear in sporadic theatrical release throughout the US marketplace -- it opens Friday in Portland, Oregon -- before its Jan. 30 DVD release. No matter what size screen you get to see it on, you'd do well to check into The Motel.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Yes, 'Two thumbs up!' made the final cut

The TV Land cable network has compiled a list of the 100 greatest catchphrases in television history, from the serious — Walter Cronkite's nightly signoff "And that's the way it is" — to the silly: "We are two wild and crazy guys!"

Kicking Christ -- and 'The Nativity' -- out of a Christmas festival

Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls: I give you Bill O'Reilly's next great crusade. (And for once, I must admit, I will share his scorn for the PCers involved.)

Sunday, November 26, 2006

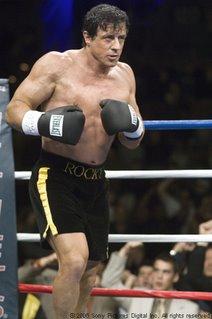

Rocky times in Iraq

On Wednesday, I got my first look at the trailer for Rocky Balboa. Later that evening, I heard more bad news about the latest casualty figures in Iraq. Ever since experiencing that bizarre confluence, I've been thinking about something Sylvester Stallone told me in 2003 -- back when many folks thought "staying the course" was a great idea. Stallone was talking about the enduring popularity of his Rocky character. But he also wanted to say something about the global influence of made-in-America pop culture -- an influence, I now fear, may diminish as the U.S. occupation continues. The money quote:

On Wednesday, I got my first look at the trailer for Rocky Balboa. Later that evening, I heard more bad news about the latest casualty figures in Iraq. Ever since experiencing that bizarre confluence, I've been thinking about something Sylvester Stallone told me in 2003 -- back when many folks thought "staying the course" was a great idea. Stallone was talking about the enduring popularity of his Rocky character. But he also wanted to say something about the global influence of made-in-America pop culture -- an influence, I now fear, may diminish as the U.S. occupation continues. The money quote:“Something like Rocky eventually gets out of your hands and becomes bigger than you personally could ever be. I’m always taken aback by how long that character has endured. I remember, when I was watching TV coverage of the Iraq War, I saw some Iraqi in some town hold up a flag with Rocky on it. And I thought, ‘You gotta be kidding me! Where did he have this flag for the past 20 years? Under his bed?’ I mean, what was he thinking? ‘Oh, yeah, the day they come here to free us, I’m gonna pull out my Rocky flag!’?”

Sunday linkage

In the New York Daily News, Elizabeth Weitzman talks with the dynamic duo of Jack Black and Kyle Gass -- a.k.a. Tenacious D -- about the mock-rockumentary Tenacious D in the Pick of Destiny. Gass: "We've determined that 83% of the movie is completely true. And the other 17% is ..." Black: "Utter lies."

Meanwhile, over at the L.A. Times, director Richard Donner claims that restoring his original version of Superman II (for DVD release this week) has allowed him to right the wrong that was done to him when he was fired by producer Ilya Salkind before he could finish the 1980 blockbuster. (Richard Lester wound up completing the sequel -- which, truth to tell, fared much better with many critics, including yours truly, than Donner's 1978 Superman: The Movie.) Times writer Geoff Boucher gives Salkind ample opportunity to respond to Donner's comments.

And when it comes to the new DVD itself -- well, Jeffrey Wells is not impressed.

Meanwhile, over at the L.A. Times, director Richard Donner claims that restoring his original version of Superman II (for DVD release this week) has allowed him to right the wrong that was done to him when he was fired by producer Ilya Salkind before he could finish the 1980 blockbuster. (Richard Lester wound up completing the sequel -- which, truth to tell, fared much better with many critics, including yours truly, than Donner's 1978 Superman: The Movie.) Times writer Geoff Boucher gives Salkind ample opportunity to respond to Donner's comments.

And when it comes to the new DVD itself -- well, Jeffrey Wells is not impressed.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Michael Moore: Voice of reason

From Michael Moore, via Anne Thompson: "Tomorrow marks the day that we will have been in Iraq longer than we were in all of World War II. That's right. We were able to defeat all of Nazi Germany, Mussolini, and the entire Japanese empire in LESS time than it's taken the world's only superpower to secure the road from the airport to downtown Baghdad."

I say that it's time to say "Cut!" and pull the plug on this project. It's over-budget, over-schedule, and likely to be a flop...

I say that it's time to say "Cut!" and pull the plug on this project. It's over-budget, over-schedule, and likely to be a flop...

Early b.o. scorecard

According to Nikki Finke, Michael Medved's least-favorite holiday movie is still raking in big bucks.

According to Nikki Finke, Michael Medved's least-favorite holiday movie is still raking in big bucks.Keillor on Altman

Garrison Keillor in the Los Angeles Times: Robert Altman "was a very young bomber pilot in World War II, and perhaps that's one reason he didn't fit into the Hollywood system. When you've flown through clouds of shrapnel and survived, you have less respect for the corporate point of view. And he was a smartass, and that didn't help. But what really made Mr. Altman an independent was the fact that he wasn't about long-term planning or risk management, he was about doing the work. He believed in taking big chances and doing it with a whole heart. He didn't mind being talked back to. He said, 'If you and I agreed about everything, then one of us is unnecessary.' But he was the captain of the ship. He didn't care for meetings in which people discuss the arc of the story and whether we need a conflict at this point or not."

Friday, November 24, 2006

Radio alert

After warming up as a talking head on MSNBC, I'm ready for the big time: On Saturday, I'll be a guest on the popular New Orleans radio program Movie Talk at around 12:15 p.m. Host Dave DuBos wants to talk about Deja Vu, the time-tripping thriller that was filmed on location in The Big Easy -- my home town! -- and you can hear us streamed live from WGSO-AM by clicking here. We'll likely also discuss the recent loss of Robert Altman and Philippe Noiret. And, again, I wouldn't be surprised if a certain subversive movie about peguins figures into the conversation.

After warming up as a talking head on MSNBC, I'm ready for the big time: On Saturday, I'll be a guest on the popular New Orleans radio program Movie Talk at around 12:15 p.m. Host Dave DuBos wants to talk about Deja Vu, the time-tripping thriller that was filmed on location in The Big Easy -- my home town! -- and you can hear us streamed live from WGSO-AM by clicking here. We'll likely also discuss the recent loss of Robert Altman and Philippe Noiret. And, again, I wouldn't be surprised if a certain subversive movie about peguins figures into the conversation.

R.I.P.: Betty Comden (1915-2006)

Alas, these things really do happen in threes. First Robert Altman, then Philippe Noiret -- and now the co-lyricist of the greatest movie musical ever made.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

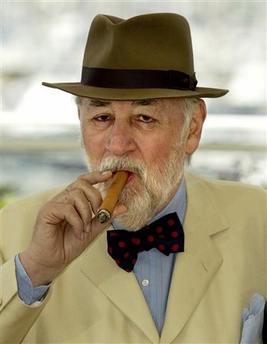

R.I.P.: Philippe Noiret (1930-2006)

Let us now praise the late, great Philippe Noiret, a consummate artist whose subtlety, versatility and emotional eloquence qualified him as one of European cinema's most valuable natural resources. As usual, GreenCine Daily provides an invaluable assortment of links to admiring appraisals. To those tributes, I humbly add the heartfelt farewell of an unabashedly starstruck fan.

Let us now praise the late, great Philippe Noiret, a consummate artist whose subtlety, versatility and emotional eloquence qualified him as one of European cinema's most valuable natural resources. As usual, GreenCine Daily provides an invaluable assortment of links to admiring appraisals. To those tributes, I humbly add the heartfelt farewell of an unabashedly starstruck fan.No kidding: I count among my most prized memories an afternoon during the 1989 Cannes Film Festival when Noiret -- looking grandly natty in a cream-colored suit – joined me for a long lunch on the patio of a posh hotel. We were supposed to chat primarily about his performance as the projectionist who brings magic and memories to a small Sicilian village in Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso (which had received a standing ovation after its festival premiere on the previous evening.) But the conversation – lubricated, I must admit, by some splendid wine – weaved and wandered lazily among other items on his lengthy resume. I tried very, very hard not to gush, and I think I may have succeeded. But if I didn’t, Noiret was too kind to make sport of me. Indeed, as we parted, he leaned over the table, looked deep into my eyes and graciously murmured: “You asked very interesting questions.” Short, dramatic pause. “And I do not say that to all of your colleagues.” I think I saw other movies, and interviewed other people, during the remainder of the festival. But I don’t remember any of them. All I recall is people asking me why I had such a goofy, glowing grin on my face.

A true international star, thanks in no small part to his fluency in English, Noiret appeared in Hollywood-financed films by Alfred Hitchcock (Topaz), George Cukor (Justine), Ted Kotcheff (Who is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe?), Peter Yates (Murphy's War) and Anatole Litvak (The Night of the Generals). But he was most moving and memorable in the European productions of such estimable auteurs as Francesco Rosi (Three Brothers), Philippe de Broca (Dear Detective), Michael Radford (Il Postino), Louis Malle (Zazie Dans Le Metro) – and, of course, Bertrand Tavernier, Noiret’s most frequent collaborator and the director of the actor’s two best films: Coup de Torchon and Life and Nothing But.

Still, it’s arguable that Noiret remains best known to U.S. audiences for Cinema Paradiso, a sentimental drama that speaks in a quiet but insistent voice to anyone who ever fell in love with (and at) the movies. When we spoke in 1989, he admitted that even he could not remain immune to the potent charm of the film’s seductive nostalgia. ''Yes,'' Noiret said, “I think all of us, we have a little bit of sadness, looking back to the great times of the movies in the theaters.'' In a similar vein, he also admitted to experiencing the occasional pang of melancholy as he remembered movie greats who were no longer with us. He was especially fond of recalling his brief collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock: ''He was so different from the image that he had . . . He was mad about food and filmmaking. So we spent our time talking about food and filmmaking . . . When people say he was bored with actors, that's not true. He was only bored with boring actors.''

Truth to tell, however, all this talk of yesterday was pretty boring to Philippe Noiret. An engagingly witty raconteur, he was never less than courteously forthcoming, and bountifully free with anecdotes, as he answered my questions about his credits. But he much preferred to talk about his new movies, and the movies yet to come.

''I'm not used to looking back to the past,'' Noiret said. ''I'm busy looking ahead, for as long as possible.'' Like most actors, he conceded, he feared each new project would be his last. But that, he added only half-jokingly, merely stoked his eagerness to pounce upon each new offer of gainful employment. ''You never know what will be the success of a film,'' he explained. ''And it's always comfortable to be making another film when you're reading terrible notices for your last film. You can say, 'Well, that's a pity, but I'm already working on another job.' It helps in your living. You see, if you're only making one film a year, or one film every year and a half, it's hard. Because when it's a failure, what do you do? What do you become? You're dead.”

Besides, he added, being a workaholic has its advantages: ''I never get bored. Tired? Sometimes. But bored? Never.''

(Directors, it should be noted, greatly appreciated Noiret’s work ethic. As Giuseppe Tornatore told me: “When you tell Philippe, 'OK, let's shoot a scene,' he'll say, 'Good! Let's play!' Because he enjoys moviemaking that much.")

Noiret was born in Lille, a northern French city near the Belgian border, in 1930. The early '50s found him in Paris, training for a theatrical career at the Centre Dramatique de l'oust. In 1953, he joined the prestigious Theatre Nationale Populaire, where he excelled for more than a decade in a diverse range of classical and contemporary roles. During this period, he also had a less prestigious but more lucrative career as a cabaret performer. ''The cabaret is a very good school for comedy,'' Noiret would say years later. ''Less austere than the theater, and more lively than the movies.''

He made his movie debut in 1956, in Agnes Varda's La Pointe Courte, and quickly attracted the attention of Louis Malle, who cast him – as a cabaret performer! -- in 1960's Zazie Dans le Metro. By 1968, he had graduated to the ranks of leading men, giving an inspired comic performance as a henpecked farmer who earns his liberation in Yves Robert's Very Happy Alexander.

''When I began to have success in the movies,'' Noiret said in 1989, ''it was a big surprise for me. For actors of my generation -- all the men of 50 or 60 now in French movies -- all of us were thinking of being stage actors. Even people like Jean-Paul Belmondo, all of us, we never thought we'd become movie stars. So, at the beginning, I was just doing it for the money, and because they asked me to do it. But after two or three years of working on movies, I started to enjoy it, and to be very interested in it. And I'm still very interested in it, because I've never really understood how it works. I mean, what is acting for the movies? I've never really understood.”

In the specific case of Philippe Noiret, screen acting was a meticulously precise art that appeared unaffectedly, and persuasively, artless. In the naturalistic, no-nonsense tradition of Spencer Tracy and Jean Gabin, Noiret created robust, full-bodied characters with a flawless professionalism that never called undue attention to itself. As I wrote in 1989: “Whether he is playing a fussy, fumbling professor (Philippe de Broca's Dear Detective), a cheerfully corrupt French cop (Claude Zidi's My New Partner), or a crafty duke who controls an under-age Louis XV (Tavernier's Let Joy Reign Supreme), Noiret doesn't appear to be acting at all. He simply is, with total conviction, and usually with the relaxed, rumpled look of an unmade bed.”

Noiret was rarely better, or more believable, than he was in Tavernier's Coup de Torchon, a 1981 psychological thriller based on a novel by the American master of hard-boiled potboilers, Jim Thompson. Tavernier re-located Thompson's story of Southern Gothic corruption to a French colony in 1938 Africa. Noiret played the anti-hero of the piece, Lucien Cordier, a lackadaisical police chief who's openly mocked by the low-lifes of his village and flagrantly cuckolded by his slovenly wife. One dark day, Cordier has an inspiration: Since everyone knows he is a coward, no one would suspect him of being a killer. So he begins a ''clean sweep'' of his village, disposing of the garbage -- brutal pimps, a wife-beating landowner, etc. -- no one will really miss. Unfortunately, Cordier gets carried away with his urban renewal program. Even more unfortunately, his resentments slowly percolate into psychosis. (Warming to the role of executioner, he announces: ''I am Jesus Christ, come back to earth with a new set of crosses!'') And yet, even at his most violent, Cordier remains, almost miraculously, a sympathetic, even vulnerable figure.

In conversation – well, OK, in the single conversation I had with him in 1989 – Noiret was reluctant to discuss his art, preferring to smile gratefully and remain silent when complimented for past achievements. But he did allow, when pressed, that the complexity of his best performances reflected his own off-screen contradictions.

''It's stupid and hard to say at the same time,'' Noiret said, ''but I certainly am an individual who is both fragile and strong -- knowing all the while that I am strong, thanks to a private victory which remains forever private.''

Some of Noiret's private life was spent at home in Carcassonne, near the Spanish border, with his wife, actress Monique Chaumette. ''How long have we been married?” he responded, chuckling at the question. “I don't remember. But we’ve lived together for 30 years now. We met when we were in the Theatre Nationale. And we have been married -- oh, I don't know, 25, 26 years.”

Revealingly, perhaps, Noiret's memory was much sharper when it came to his movie credits. Cinema Paradiso, he said, was his 99th film. Bertrand Tavernier’s Life and Nothing But was his 100th. And, to my mind, his greatest.

Noiret stars to perfection as Major Dellaplane, a career army officer who, during the aftermath of World War I, is obsessed with totaling the exact number of French casualties, and identifying the thousands of French soldiers listed as missing in action. For Dellaplane, the arduous task means keeping countless files, photographing and interviewing hundreds of shell-shocked patients in military hospitals, and personally visiting excavation sites where great numbers of fallen soldiers can be unearthed. A phrase uttered by an amnesiac, a watch or a cup found on a corpse, a letter from home uncovered near a battlefield -- any of these can end a family's long uncertainty, and close one of Dellaplane's files.

But there is always another file, another family. And Dellaplane is running out of time.

Tavernier once explained to me that he modeled Dellaplane after the gruff but compassionate cavalry officer played by John Wayne in John Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. And, indeed, Noiret plays the French officer with much the same moral authority, virile humor and hard-won wisdom that Wayne conveyed so vividly as Capt. Nathan Cutting Brittles. (When someone chides him for his brutal bluntness while telling a woman of her lover’s death, Dellaplane explains that the best way to deliver such bad news is “by stunning her. You have to strike once, so hard it's like a nightmare. Later you wake up and life seems gentler.”) If Dellaplane seems more contemptuous of his superiors than Brittles ever appeared, and more bitter about the absurdities of battle, well, he has good reason: Dellaplane's office has been ordered to find a French casualty who cannot be identified, to provide an ''unknown soldier'' to be enshrined at the Arc de Triomphe. For Dellaplane, the mission is a terrible charade -- an attempt to divert attention from thousands by focusing on an individual -- and a ridiculous distraction from his duty to end the desperate searches of families and loved ones.

There is a sharply satirical edge to the humor that laces the drama of Life and Nothing But. A sculptor expresses his great joy that, with so many towns ordering monuments to war dead, he will never be wanting for work. Villagers plot to change their boundaries, just so they, too, can claim fallen heroes as their own. Better still, there is a refreshing lack of melodramatic overstatement, in the storytelling as well as the performances. Tavernier never shows us a body, never exploits anyone's anguish. At one point, loved ones file onto a former battlefield to inspect the personal effects of dead soldiers. They don't cry, they don't even appear to be mad anymore. They simply want to bury the dead, so they can get on with life.

Much of Life and Nothing But focuses on Dellaplane's relationship with two women searching for their missing men. Alice (Pascale Vignal) is a young provincial schoolteacher whose fiancé never returned from the war. Dellaplane responds to her as a fond but stern uncle, warning her that, all things considered, she would be better off forgetting her missing soldier. Irene (Sabine Azema) is an aristocratic Parisian whose husband was wounded in combat, and then, apparently, disappeared without a trace. Dellaplane responds to her as -- well, he doesn't quite know how to respond to her.

Tavernier generates suspense and a subdued but palpable erotic tension as he continually allows Irene and Dellaplane to cross paths. Ultimately, she confronts him with a challenge more daunting than any he has ever faced in battle.

And that's when Dellaplane, a man so accustomed to death, must prove he has the courage for a new life.

Life and Nothing But is a great movie, with a great performance at its center. Philippe Noiret is dead. Long live Philippe Noiret.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

TV Alert!

Set your alarm or your VCR! I'll be chatting with the lovely and talented Alex Witt about holiday movies on MSNBC tomorrow morning -- yes, Thanksgiving Day! -- during the half-hour blocks starting at 8:30 and 10:30 CST. (That's 9:30 and 11:30 EST.) Don't be surprised if a certain subversive movie about penguins enters into the conversation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)