Let us now praise the late, great Philippe Noiret, a consummate artist whose subtlety, versatility and emotional eloquence qualified him as one of European cinema's most valuable natural resources. As usual, GreenCine Daily provides an invaluable assortment of links to admiring appraisals. To those tributes, I humbly add the heartfelt farewell of an unabashedly starstruck fan.

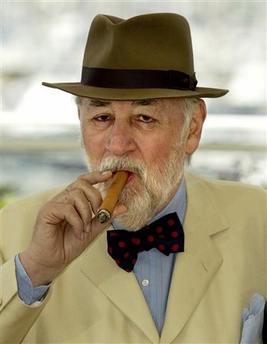

Let us now praise the late, great Philippe Noiret, a consummate artist whose subtlety, versatility and emotional eloquence qualified him as one of European cinema's most valuable natural resources. As usual, GreenCine Daily provides an invaluable assortment of links to admiring appraisals. To those tributes, I humbly add the heartfelt farewell of an unabashedly starstruck fan.No kidding: I count among my most prized memories an afternoon during the 1989 Cannes Film Festival when Noiret -- looking grandly natty in a cream-colored suit – joined me for a long lunch on the patio of a posh hotel. We were supposed to chat primarily about his performance as the projectionist who brings magic and memories to a small Sicilian village in Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso (which had received a standing ovation after its festival premiere on the previous evening.) But the conversation – lubricated, I must admit, by some splendid wine – weaved and wandered lazily among other items on his lengthy resume. I tried very, very hard not to gush, and I think I may have succeeded. But if I didn’t, Noiret was too kind to make sport of me. Indeed, as we parted, he leaned over the table, looked deep into my eyes and graciously murmured: “You asked very interesting questions.” Short, dramatic pause. “And I do not say that to all of your colleagues.” I think I saw other movies, and interviewed other people, during the remainder of the festival. But I don’t remember any of them. All I recall is people asking me why I had such a goofy, glowing grin on my face.

A true international star, thanks in no small part to his fluency in English, Noiret appeared in Hollywood-financed films by Alfred Hitchcock (Topaz), George Cukor (Justine), Ted Kotcheff (Who is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe?), Peter Yates (Murphy's War) and Anatole Litvak (The Night of the Generals). But he was most moving and memorable in the European productions of such estimable auteurs as Francesco Rosi (Three Brothers), Philippe de Broca (Dear Detective), Michael Radford (Il Postino), Louis Malle (Zazie Dans Le Metro) – and, of course, Bertrand Tavernier, Noiret’s most frequent collaborator and the director of the actor’s two best films: Coup de Torchon and Life and Nothing But.

Still, it’s arguable that Noiret remains best known to U.S. audiences for Cinema Paradiso, a sentimental drama that speaks in a quiet but insistent voice to anyone who ever fell in love with (and at) the movies. When we spoke in 1989, he admitted that even he could not remain immune to the potent charm of the film’s seductive nostalgia. ''Yes,'' Noiret said, “I think all of us, we have a little bit of sadness, looking back to the great times of the movies in the theaters.'' In a similar vein, he also admitted to experiencing the occasional pang of melancholy as he remembered movie greats who were no longer with us. He was especially fond of recalling his brief collaboration with Alfred Hitchcock: ''He was so different from the image that he had . . . He was mad about food and filmmaking. So we spent our time talking about food and filmmaking . . . When people say he was bored with actors, that's not true. He was only bored with boring actors.''

Truth to tell, however, all this talk of yesterday was pretty boring to Philippe Noiret. An engagingly witty raconteur, he was never less than courteously forthcoming, and bountifully free with anecdotes, as he answered my questions about his credits. But he much preferred to talk about his new movies, and the movies yet to come.

''I'm not used to looking back to the past,'' Noiret said. ''I'm busy looking ahead, for as long as possible.'' Like most actors, he conceded, he feared each new project would be his last. But that, he added only half-jokingly, merely stoked his eagerness to pounce upon each new offer of gainful employment. ''You never know what will be the success of a film,'' he explained. ''And it's always comfortable to be making another film when you're reading terrible notices for your last film. You can say, 'Well, that's a pity, but I'm already working on another job.' It helps in your living. You see, if you're only making one film a year, or one film every year and a half, it's hard. Because when it's a failure, what do you do? What do you become? You're dead.”

Besides, he added, being a workaholic has its advantages: ''I never get bored. Tired? Sometimes. But bored? Never.''

(Directors, it should be noted, greatly appreciated Noiret’s work ethic. As Giuseppe Tornatore told me: “When you tell Philippe, 'OK, let's shoot a scene,' he'll say, 'Good! Let's play!' Because he enjoys moviemaking that much.")

Noiret was born in Lille, a northern French city near the Belgian border, in 1930. The early '50s found him in Paris, training for a theatrical career at the Centre Dramatique de l'oust. In 1953, he joined the prestigious Theatre Nationale Populaire, where he excelled for more than a decade in a diverse range of classical and contemporary roles. During this period, he also had a less prestigious but more lucrative career as a cabaret performer. ''The cabaret is a very good school for comedy,'' Noiret would say years later. ''Less austere than the theater, and more lively than the movies.''

He made his movie debut in 1956, in Agnes Varda's La Pointe Courte, and quickly attracted the attention of Louis Malle, who cast him – as a cabaret performer! -- in 1960's Zazie Dans le Metro. By 1968, he had graduated to the ranks of leading men, giving an inspired comic performance as a henpecked farmer who earns his liberation in Yves Robert's Very Happy Alexander.

''When I began to have success in the movies,'' Noiret said in 1989, ''it was a big surprise for me. For actors of my generation -- all the men of 50 or 60 now in French movies -- all of us were thinking of being stage actors. Even people like Jean-Paul Belmondo, all of us, we never thought we'd become movie stars. So, at the beginning, I was just doing it for the money, and because they asked me to do it. But after two or three years of working on movies, I started to enjoy it, and to be very interested in it. And I'm still very interested in it, because I've never really understood how it works. I mean, what is acting for the movies? I've never really understood.”

In the specific case of Philippe Noiret, screen acting was a meticulously precise art that appeared unaffectedly, and persuasively, artless. In the naturalistic, no-nonsense tradition of Spencer Tracy and Jean Gabin, Noiret created robust, full-bodied characters with a flawless professionalism that never called undue attention to itself. As I wrote in 1989: “Whether he is playing a fussy, fumbling professor (Philippe de Broca's Dear Detective), a cheerfully corrupt French cop (Claude Zidi's My New Partner), or a crafty duke who controls an under-age Louis XV (Tavernier's Let Joy Reign Supreme), Noiret doesn't appear to be acting at all. He simply is, with total conviction, and usually with the relaxed, rumpled look of an unmade bed.”

Noiret was rarely better, or more believable, than he was in Tavernier's Coup de Torchon, a 1981 psychological thriller based on a novel by the American master of hard-boiled potboilers, Jim Thompson. Tavernier re-located Thompson's story of Southern Gothic corruption to a French colony in 1938 Africa. Noiret played the anti-hero of the piece, Lucien Cordier, a lackadaisical police chief who's openly mocked by the low-lifes of his village and flagrantly cuckolded by his slovenly wife. One dark day, Cordier has an inspiration: Since everyone knows he is a coward, no one would suspect him of being a killer. So he begins a ''clean sweep'' of his village, disposing of the garbage -- brutal pimps, a wife-beating landowner, etc. -- no one will really miss. Unfortunately, Cordier gets carried away with his urban renewal program. Even more unfortunately, his resentments slowly percolate into psychosis. (Warming to the role of executioner, he announces: ''I am Jesus Christ, come back to earth with a new set of crosses!'') And yet, even at his most violent, Cordier remains, almost miraculously, a sympathetic, even vulnerable figure.

In conversation – well, OK, in the single conversation I had with him in 1989 – Noiret was reluctant to discuss his art, preferring to smile gratefully and remain silent when complimented for past achievements. But he did allow, when pressed, that the complexity of his best performances reflected his own off-screen contradictions.

''It's stupid and hard to say at the same time,'' Noiret said, ''but I certainly am an individual who is both fragile and strong -- knowing all the while that I am strong, thanks to a private victory which remains forever private.''

Some of Noiret's private life was spent at home in Carcassonne, near the Spanish border, with his wife, actress Monique Chaumette. ''How long have we been married?” he responded, chuckling at the question. “I don't remember. But we’ve lived together for 30 years now. We met when we were in the Theatre Nationale. And we have been married -- oh, I don't know, 25, 26 years.”

Revealingly, perhaps, Noiret's memory was much sharper when it came to his movie credits. Cinema Paradiso, he said, was his 99th film. Bertrand Tavernier’s Life and Nothing But was his 100th. And, to my mind, his greatest.

Noiret stars to perfection as Major Dellaplane, a career army officer who, during the aftermath of World War I, is obsessed with totaling the exact number of French casualties, and identifying the thousands of French soldiers listed as missing in action. For Dellaplane, the arduous task means keeping countless files, photographing and interviewing hundreds of shell-shocked patients in military hospitals, and personally visiting excavation sites where great numbers of fallen soldiers can be unearthed. A phrase uttered by an amnesiac, a watch or a cup found on a corpse, a letter from home uncovered near a battlefield -- any of these can end a family's long uncertainty, and close one of Dellaplane's files.

But there is always another file, another family. And Dellaplane is running out of time.

Tavernier once explained to me that he modeled Dellaplane after the gruff but compassionate cavalry officer played by John Wayne in John Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. And, indeed, Noiret plays the French officer with much the same moral authority, virile humor and hard-won wisdom that Wayne conveyed so vividly as Capt. Nathan Cutting Brittles. (When someone chides him for his brutal bluntness while telling a woman of her lover’s death, Dellaplane explains that the best way to deliver such bad news is “by stunning her. You have to strike once, so hard it's like a nightmare. Later you wake up and life seems gentler.”) If Dellaplane seems more contemptuous of his superiors than Brittles ever appeared, and more bitter about the absurdities of battle, well, he has good reason: Dellaplane's office has been ordered to find a French casualty who cannot be identified, to provide an ''unknown soldier'' to be enshrined at the Arc de Triomphe. For Dellaplane, the mission is a terrible charade -- an attempt to divert attention from thousands by focusing on an individual -- and a ridiculous distraction from his duty to end the desperate searches of families and loved ones.

There is a sharply satirical edge to the humor that laces the drama of Life and Nothing But. A sculptor expresses his great joy that, with so many towns ordering monuments to war dead, he will never be wanting for work. Villagers plot to change their boundaries, just so they, too, can claim fallen heroes as their own. Better still, there is a refreshing lack of melodramatic overstatement, in the storytelling as well as the performances. Tavernier never shows us a body, never exploits anyone's anguish. At one point, loved ones file onto a former battlefield to inspect the personal effects of dead soldiers. They don't cry, they don't even appear to be mad anymore. They simply want to bury the dead, so they can get on with life.

Much of Life and Nothing But focuses on Dellaplane's relationship with two women searching for their missing men. Alice (Pascale Vignal) is a young provincial schoolteacher whose fiancé never returned from the war. Dellaplane responds to her as a fond but stern uncle, warning her that, all things considered, she would be better off forgetting her missing soldier. Irene (Sabine Azema) is an aristocratic Parisian whose husband was wounded in combat, and then, apparently, disappeared without a trace. Dellaplane responds to her as -- well, he doesn't quite know how to respond to her.

Tavernier generates suspense and a subdued but palpable erotic tension as he continually allows Irene and Dellaplane to cross paths. Ultimately, she confronts him with a challenge more daunting than any he has ever faced in battle.

And that's when Dellaplane, a man so accustomed to death, must prove he has the courage for a new life.

Life and Nothing But is a great movie, with a great performance at its center. Philippe Noiret is dead. Long live Philippe Noiret.

3 comments:

What an absolutely magnificent tribute. Glad you discussed Coup de Torchon, which I saw last year. It is a brilliant movie, in large measure because of Noiret. I plan to show your post to my husband, who is French and feeling the loss this morning. This is my first time visiting your blog (via GreenCine) and I plan to return.

Ditto: Great tribute to a grand actor.

I recently saw Life and Nothing But, and really loved Noiret's performance... in the exchange of glances between him and Sabine Azema in the "show for the troops" scene is beautifully conveyed and extremely effective in its understatement... One thinks how Dellaplante can see the ugly face of death, but can't face love without trembling.

...And a fine film by Tavernier, too:! I also love his other film on WW1 subject "Capitaine Conan", with an excellent Phillipe Torreton

Magnifique. A lovely, touching, and humorous tribute to a great figure in French cinema. Beautifully written, thank you for sharing. - dmd, la.

Post a Comment