Before the intense Sonny Crockett zipped through a pastel-colored Miami to a techno-rock beat, there was Lee Marvin, in living black and white, as Lt. Frank Ballinger, a savagely single-minded Chicago cop who blasted away killers to the tune of percussive jazz in M Squad (1957-60).

Before the intense Sonny Crockett zipped through a pastel-colored Miami to a techno-rock beat, there was Lee Marvin, in living black and white, as Lt. Frank Ballinger, a savagely single-minded Chicago cop who blasted away killers to the tune of percussive jazz in M Squad (1957-60).Before bad-ass rappers and black-hatted country boys began to strut their stuff in image-enhancing music videos, there was Lee Marvin, in Richard Brooks' aptly titled The Professionals (1966), playing Henry Fardan, a steely-eyed tactician who's so glacially cool that, throughout most of a long ride across the blazing Mexican desert, he keeps his shirt buttoned up to the neck.

And before Arnold Schwarzenegger cut a relentless path of destruction through Los Angeles in The Terminator, there was Lee Marvin, offering the definitive portrait of an obsessed man of violence who will let nothing -- not even, apparently, his own mortality -- impede his implacable force of vengeful will in John Boorman's classic Point Blank (1967).

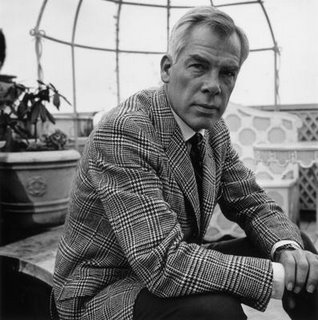

Mortality finally caught up with Lee Marvin 19 years ago this month when he died at age 63. But he remains immortal on film and videocassette -- and in cable-TV retrospectives like the Sunday marathon on Turner Classic Movies -- where he can be seen time and again as a ferocious force of nature barely contained, ever ready to erupt. Lean and leathery, he was an actor who could threaten with a beaming smile, who could deliver a death sentence with a casual shrug.

In The Killers (1964), he gave one of his greatest performances as Charlie Strom, a soft-spoken hit man who brutally interrogates a sultry femme fatale (Angie Dickinson) with the insinuating murmur of a considerate lover. Late in the film, after Marvin realizes he's been betrayed by Dickinson and (no kidding) Ronald Reagan, he holds the treacherous pair at gunpoint. Dickinson frantically begins to explain why Marvin was set up, why she helped another hit man lie in wait for him. But Marvin, fatally wounded, cuts her short. With the weary impatience of someone who has lived too long and killed too often, he shakes his head slightly and says: ''Lady, I just haven't got the time.''

Blam! Blam! End of conversation.

Marvin began his film career as a kind of general-purpose psychopath, embodying an evil so mindless and malevolent that his defeat or demise would guarantee audience cheers. M Squad, one of the most violent shows in the history of TV, nudged him slightly toward more heroic roles -- though, truth to tell, it was difficult to see much difference between his mayhem as a movie villain and his crimefighting as a prime-time cop. But it was not until his Oscar-winning comic turn in Cat Ballou (1965) that Marvin was embraced as a leading man by moviegoers. Or, to be more precise, he was warily accepted, much the same way you might accept as a house pet a mountain lion that supposedly has been domesticated.

He was lots of fun as a drunken gunfighter (and the drunk's deadlier brother) in Cat Ballou, particularly when he stumbled into the funeral for the very man he was hired to protect. (Seeing a row of lit candles, he smiled a goofy grin and proceeded to sing: ''Happy birthday to you . . .'') But then the time came for the comical drunk to sober up and strap on his six guns. When he did, nobody was laughing.

After he became a star, alas, Marvin occasionally was guilty of lazy, obviously alcohol-influenced performances. In such turkeys as The Klansman (1975), with Richard Burton (and, no kidding, O.J. Simpson), and Avalanche Express (1979), with Robert Shaw, he behaved on screen very much like someone who felt rudely interrupted from a more important off-screen task (i.e., drinking his co-stars under a table). In later years, however, Marvin seemed to snap out of his self-indulgent slump, with performances ranging from the no-frills professionalism of his Royal Canadian Mountie in Death Hunt (1981) to the elegant bravado of his vaguely sinister businessman in Gorky Park (1983). In Death Hunt, Marvin has a great moment where he tries to talk fugitive Charles Bronson into surrendering -- while Bronson holds a shotgun just inches away from Marvin's starkly chiseled face. Marvin, not surprisingly, manages to maintain his cool during the tense situation.

But if he's cool in Death Hunt, he's practically sub-zero in Gorky Park, suave and self-assured in the face of what he views as the clumsy investigative efforts of a Moscow police detective (William Hurt). After completing the movie, Marvin complained to an interviewer (well, OK, he bitched to me) about a scene where Hurt keeps raising his voice during their conversation about a murder case. Marvin thought Hurt was trying to upstage him. But even if he was, the scene works even better that way: There's Hurt, struggling to come on macho and masterful even as he knows he's on thin ice; and there's Marvin, who's too contemptuously smug to feel the need to raise his voice.

Marvin's authoritative underplaying served him well in a variety of heroic parts -- especially as the commanding officers in The Dirty Dozen (1967), Robert Aldrich's revisionist yet rousing World War II adventure, and The Big Red One (1979), Samuel Fuller's autobiographical drama of wartime service in Europe. (Marvin, an ex-Marine, could be quite persuasive as a military man.) At his frequent best, he could convey a moral dimension without seeming preachy, and an impatience with stupidity without being short-tempered. In The Professionals, Ralph Bellamy -- who hires Marvin, Burt Lancaster, Robert Ryan and Woody Stride for a dangerous rescue mission -- asks if Marvin has "any objections to working with a Negro'' (Strode). Marvin waits a few seconds before speaking, but his expression is easy to read: ''What the hell kind of damn fool question is that?'' When Marvin finally does speak, he pointedly ignores Bellamy's query -- there are more important matters to discuss.

Yes indeed, Lee Marvin could be tough. (In Point Blank, he made movie history of sorts by being the first star to -- ouch! -- slug another man in the groin.) Yet he could also be affectingly poignant as the broken-down baseball player in Ship of Fools (1965). And he was nothing less than brilliant as Hickey, Eugene O'Neill's haunted and haunting traveling salesman, in John Frankenheimer's under-rated film version of The Iceman Cometh (1973). At the very end of Iceman, Hickey must drop the veneer of loquacious charisma, must end his self-deluding efforts to dispel the pipedreams of his cronies, to unleash a volcanic rage that horrifies even Hickey himself. Marvin roars the words -- ''You know what you can do with your pipedreams now, you damned bitch!" -- then recoils in pain, despair, self-disgust. For once, the self-possessed control freak has let down his guard, and the demons have been set loose. And it suits O'Neill's drama perfectly. Or, as critic Stanley Kauffmann put it: ''Marvin was born to play Hickey.''

Maybe. Or maybe, more likely, Lee Marvin was born to just give everyone, himself included, a damn good time at the movies. ''I would like to entertain an audience,'' he told me during a 1981 interview. ''I've done the heavy films, the truthful ones. And once in a while, they get too depressing for an audience.''

(An ironic sidebar: During our conversation, I kidded him about "shooting President Reagan" back in 1964's The Killing. "Yeah," responded with a wolfish grin, "but he wasn't President yet when I shot him." The very next day, John Hinckley tried to gatecrash into history by taking aim at the Commander in Chief.)

For all his independence, on screen and off, Marvin confessed to a nostalgia for the old, autocratic days of Hollywood, when only moguls in charge of studios were to be taken seriously.

''It took a lot of thinking away from you,'' Marvin said. ''You didn't have to twist and turn at night, wondering what line you were going to say the next day. Because they'd already written it. You just came to work, kept your mouth shut, got your job done and went home -- with a check.''

There was a comforting simplicity in all that, Marvin said. The sort of simplicity a true professional could appreciate.

No comments:

Post a Comment